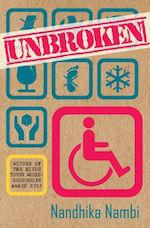

Sixteen year old Akriti’s life is dark and gloomy: her father is the most selfish person in the world, her mother the most ignorant, her brother Ranjith too goody-two-shoes, her teachers the most boring and her friends Karthik and Preethi the most annoying. In addition to these woes, she is wheelchair-bound. To appear “unbroken”, Akriti creates a fortress around her: loud music on ipod, overeating, strong opinions, harsh words, sleep and avoidance. Her room on the first floor of her home and her seat on the last desk in her class as spatial metaphors of emotional distance and disconnect from all around her. Is Akriti’s definition of “unbroken” correct or would she have to change it?

Unbroken by Nadhika Nambi is a coming-of-age book which packs within itself rich themes of disability and empowerment, and denial and acceptance. While the first person stream of consciousness narration intimately records the minute workings of Akriti’s mind without authorial judgement, it also subtly exposes the self-centredness of her perception. The result is a balanced complex portrayal of a physically disabled sixteen year old who is not entirely different from other youngsters but whose challenges are also not absolutely similar to the others of her age. We as readers, sway between adoration and disapprobation. We love Akriti’s rebellious independence and gritty refusal to take help from anyone, but we can also see how she uses her disability trump card to her advantage at right junctures because it makes her feel “empowered”. Though we do not approve of Akriti’s ego trips, we still empathise with her and are sensitised towards her challenges.

Richly interwoven is the underlined message is that physical disability constrains but it is attitudinal disability that cripples. While unwavering patience and unflinching love of family are important in overthrowing these barriers, participation too is deemed important: “It was impossible to get one’s arms around someone in a wheelchair unless they moved forward cooperatively”.

Filtered through Akriti’s mind come alive the ethos of urban middle-class Indian household and modern school-life: the taste of home-cooked savoury dishes on the table and in the tiffin and clamour of chattering relatives and classrooms, the sights of the school corridors and slick malls and the trauma of nosy cousins and unfinished homework.

The book will resonate with any young adult (both able and differently-abled) battling teenage issues ranging from pimples to career choice. Also, highly recommended for adults who feel the need to dust the cobwebs inside them. After all, as C.S. Lewis says, “A children's story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children's story in the slightest”.